Aid agencies across the UK are reeling from Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s surprise announcement this week to increase military spending at the expense of foreign aid, writes Maxine Betteridge-Moes for the New Internationalist.

On 25 February, Starmer said defence spending would rise to 2.5 per cent of GDP by 2027 – three years earlier than planned. He also backpedalled on his own criticisms of aid cuts under the previous Conservative government, as well as the Labour party’s election manifesto to restore the UK aid budget to 0.7 per cent of gross national income. Instead, Starmer slashed it from 0.5 per cent to 0.3 per cent, drawing objections from his own cabinet members, as well as from political opposition.

Romilly Greenhill, the CEO of Bond, a network of UK NGOs working in international development, called the decision ‘short-sighted and appalling’.

‘My head hurts and my heart hurts,’ says Danny Sriskandarajah, CEO of the New Economic Foundation, a UK thinktank. ‘This is the moment in human history where we need to have proper international collaboration if we’re to solve any of the big challenges that face us as a species. And here we go again: a government that was elected on a promise of being a responsible internationalist and protecting the aid budget, now reneging on those commitments.’

It’s too early to know exactly how these cuts will impact programmes on-the-ground, but the government’s own assessment following smaller cuts in 2021 shows a disproportionate and devastating impact on women and girls.

Our economic model is broken

Amidst this week’s discussions, much of the mainstream media has failed to analyze these international aid cuts as yet another symptom of a broken economic model whereby politicians exploit voters’ economic grievances by redirecting public frustrations toward marginalized communities. Instead, they have championed the likes of Foreign Secretary David Lammy who published an op-ed in The Guardian this week arguing that the government needs to ‘balance the compassion of our internationalism with the necessity of our national security’.

Putting aside the mounting pile of evidence that both Lammy and Starmer are completely devoid of morality and integrity, these repeated claims of making ‘tough decisions’ in the name of national security demand interrogation.

These latest cuts to the UK aid budget did not happen in a vacuum; US President Donald Trump’s 90 day freeze on foreign aid threw the sector into chaos earlier this year. But rightwing leaders of other major donors including the Netherlands, Sweden and Belgium have all slashed their foreign aid budgets as well. Germany, which saw the far right AfD party double its vote share in last week’s elections, is also expected to announce similar measures. Starmer has capitulated to this trend.

‘The Labour government is basically trying to out-rightwing the Right by this peace through strength claim,’ says Anna Stavrianakis, a professor of international relations at the University of Sussex, and director of research and strategy at Shadow World Investigations, an organization that investigates the arms trade. ‘The UK could be shoring up multilateralism and the development system to take hold of the transformation of global order that’s happening at the moment. But instead, they’re throwing their lot in with a proto fascist leader in the United States and sending more money to the pockets of the arms companies and their shareholders.’

Starmer will meet with Trump in Washington this week, where they are likely to discuss more opportunities for weapons contracting – something the UK’s own defence workers’ union has criticized. The UK already buys 89 per cent of its weapons from the US.

A tarnished reputation

The UK’s approach to international aid shifted in 2020 when then Conservative Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, announced a merger between the Department of Foreign and International Development (DFID) and the Foreign, Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO) – what Michael Jennings, a development professor at SOAS University of London called a ‘wanton act of destruction’.

‘Without a DFID, without an independent minister for aid, there is no one fighting the corner. There is no one to say, “Actually this should be given a higher priority”,’ says Jennings of the Labour government’s latest cuts. ‘We are at a critical juncture that does raise those questions about what might an alternative look like from the perspective of a country in the Global South.’

A lack of transparency around the use of the aid budget has contributed to public scepticism of its efficacy – an issue acknowledged by many in the sector. The latest data from the Independent Commission for Aid Impact shows that the amount of aid spent on hosting refugees and asylum seekers in the UK reached £4.3 billion ($5.4 billion) in 2023 – up from £3.7 billion ($4.6 billion) in 2022.

‘There is a disconnect between a system that was designed to alleviate poverty in the poorest countries, to the way that it currently works,’ says Sriskandarajah of the New Economic Foundation. ‘There needs to be a democratic accountability for [the Labour government’s] decision. We need to do a better job of making arguments for why the aid system is important, and the aid system does need to become more efficient.’

For Sriskandarajah simply cutting the aid budget without making structural changes to the distribution of aid creates a ‘perverse situation where the less income you have, the more expensive and cumbersome the interventions are because you can’t invest in the more durable, sustainable solution’.

Mark Curtis, the director of Declassified UK, argues that it’s about more than reform.

‘I don’t think that NGOs and others should be calling to reform UK aid but to call for a withdrawal of UK influence in developing countries,’ he says. ‘Aid money from the UK should be delivered through multilateral institutions and NGOs over which the UK government should have no influence.’

Curtis and many other progressive commentators argue that the prime minister could have found other, fairer ways to raise funds, through measures like a wealth tax. Research by the Tax Justice Network has established that a two per cent levy on individuals who own assets worth more than £10 million could raise £24 billion a year ($30 billion).

‘The problem is human security’

Ultimately, what we need is a global economic system that doesn’t continue to perpetuate the world’s inequalities, while also addressing the reasons that they are there in the first place.

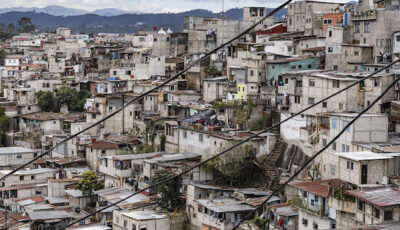

The debt burden among many poor countries in the Global South has been rising in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, while foreign investment has slowed. The historical and ongoing extractivist nature of much of the Western economy has left many leaders in the Global South unable to actively influence the policy direction of their countries, thereby contributing to a cycle of aid dependency and an increase in forced displacement as a result of climate change disasters and conflicts.

Far from acts of benevolence, many poorer countries are in fact owed reparations. While some see international aid as part of this, what international aid money is used for is still largely decided by the countries giving it. Reparations on the other hand, wouldn’t come with the same strings. But Starmer has rejected calls for slavery reparations talks, saying the country instead needed to focus on ‘current future-facing challenges’ instead of ‘spend a lot of time on the past’.

It seems that boosting the defence sector is part of this focus, under the guise of keeping people safer in an increasingly dangerous world. But Vijay Prashad, the executive director of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research, says this is a matter of a political choice: ‘[The UK] seems paralyzed by people coming in on small boats across the channel, desperate people. That has created a total sense of political paralysis … [the government’s] biggest problem is actually human security – people can’t afford to live.’

UK defence spending is already high. Last year, the government spent £53.9 billion on defence ($68 billion) – more than four times what it spent on aid. Khem Rogaly of Common Wealth pointed out in an interview for LBC on Wednesday that the UK military budget is larger now, in real terms, than in 1980 at the height of the Cold War.

‘People often talk about defence, diplomacy and development as a three-legged stool,’ says Gideon Rabinowitz, the director of Policy and Advocacy at Bond, a network of UK NGOs working in international development. ‘What does that stool look like now, when you’re cutting even more off the shortest leg?’

Profiting from war

A further increase in military spending will come as good news for arms the industry.

‘Defence spending is a really inefficient way to stimulate economic growth, because it is basically putting money into the pockets of the shareholders of the arms companies,’ says Stavrianakis. ‘It’s a transfer of wealth away from the world’s poorest into the pockets of the world’s richest.’

The market value of military equipment manufacturers in the US and Europe increased by nearly 60 per cent between February 2022 and March 2024, thanks to the wars in Ukraine and Palestine. In 2023 global military expenditure reached $2,443 billion, up nearly seven per cent from 2022 – the ninth consecutive annual rise.

‘More militarization is not the answer to the crises we face,’ says Liz McKean, the director of Campaigns, Policy and International Programmes at War on Want. ‘It will pour more taxpayer money into the coffers of deadly and polluting arms companies, which are already profiteering from conflicts.’

Defence spending is also unpopular among many voters. The last year in particular has seen an explosion of activism against the arms industry in the UK and around the world. Last week over 230 global civil society organizations made a public call for governments producing F-35 fighter jets to immediately halt all arms transfers to Israel. The Danish government also faced trial this week after it was sued by a group of human rights organizations who argue that arms sales to Israel will have contributed to possible war crimes in Gaza.

‘I think a lot of people can feel very disempowered when they see what’s happening at a national level or internationally, to which I would say, turn your attention to look locally. A lot of this is about building connections, organizing and forming communities that can then feel confident in making demands,’ says Stavrianakis.

On 27 February, 138 leaders of the UK international NGO sector signed an open letter to the prime minister and the treasury demanding a reversal of its decision to cut the UK aid budget. The same day, a Trump official said the US government was ‘very pleased’ about the increase in UK defence spending.

Stavrianakis says this week’s events should serve as a sign of what’s to come under the current UK Labour government and amid the surge of far right politics globally.

‘I think it’s a lesson to pay attention to the signs instead of being grateful that we’ve kicked the Tories out. I think it’s a wake up call to the development sector to start radicalizing their political and economic demands.’

Maxine is the digital editor at New Internationalist.

Original source: New Internationalist

Image credit: Some rights reserved by DFID, flickr creative commons